I watched the movie for the first time on the strength of its title. It has that touch of magic you want, some mysterious attraction behind words that lure you in: The Remains of the Day. It could mean anything, but it sounded like a requiem, whatever is left after everything else has gone away. Life imparts that feeling, always going away but leaving time to do what you'd intended; the remainder will give you that much, at least. I wanted to find out what remained. By now I have watched the movie twenty times if I have watched it once. I am a fan. Two instances led me from the movie to the book, which I was aware of but had guessed wrong about. I assumed the movie’s legendary producers, Merchant and Ivory, had mined the gems out of a minor story. That was incorrect: the book had done nearly all of the work. The first signpost on the road to the novel popped up during a conversation that consisted largely of myself haranguing a friend, a government attorney, on what made the movie great. He took the chance to pass along a bit of wisdom he'd been given, that the book was excellent too, but different from the movie. That turned out to be partially right. The book is better than just excellent, but the movie is a near-exact copy. Almost nothing is changed. The book gives you more, but not by a lot. It must be one of the best adaptations ever made and a semi-rare case where an author is happy with what changes were hacked and grafted into his art. The second major moment on the way to picking up the book was when its author, Kazuo Ishiguro, was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. Several months afterward I walked into a bookstore in Ann Arbor, Michigan and Ishiguro’s books were set out on display on a table in front of the shop. I bought a copy. Why not—am I too good to try the man awarded a Nobel Prize for his craft? I read the book in two sittings and came here to write this . . . . . review . . . . . this salute . . . . . this homage. I do not know what this is, but I am driven to write it. The bare bones of the story lay out what a professional butler heard, saw, and indirectly participated in over the course of thirty years loyal service at the manor house of an English Lord Darlington. Odd—surely—and maybe on its face even a boring subject, but the timeline covers the period following World War I, with the rise of the Nazis in Germany, and finishes about ten years after the conclusion of World War II. Much of this happens right under the nose of the butler, Stevens, with him a wallflower to completely astonishing, century-shaping machinations. The butler is a strange chap. One of the oddest I have ever encountered. He lived by a simple (and nebulous) credo that states a butler must, at all times, “Be possessed of a dignity in keeping with his position.” This foggy maxim, under Steven’s interpretation, becomes an effective call both to an almost complete amorality, and the extreme suppression of any need to engage in a normal emotional interaction with human kind. As he makes clear to the housekeeper, Miss Kenton, his belief that a butler may only call his life well lived once he is certain he has effectively annihilated his own humanity in the service of his employer. At one point, Stevens says it like this: “My vocation will not be fulfilled until I have done all I can to see his lordship through the great tasks he has set himself. The day his lordship’s work is complete, the day he is able to rest on his laurels, content in the knowledge that he has done all anyone could ever reasonably ask of him, only on that day, Miss Kenton, will I be able to call myself, as you put it, a well-contented man." Miss Kenton, often stunned by the fanatic zeal of Stevens, is a fine woman, and she finds herself in love with self-possessed chief butler and his well-ordered house. She mistakenly believes there is something to discover behind the outward mystery. And Stevens, if he had access to his own emotions, would have realized he was in love with Kenton, too. But he never could get there. It is one of the devastating narrative threads in the book. Having as his only passion in life his profound belief in the butler's credo, Stevens leads the most unscratchably blank-slate-of-an-existence imaginable, learning nothing about human nature and truly getting to know no-one: not Miss Kenton, not his father, not Lord Darlington. It is the English emotional reserve, which Stevens is conscious of as a high virtue, taken to an almost absurd but completely believable extreme. The more Stevens gets to care about someone, the further his emotions run and hide from him and, even more, the less he is able to discern what is happening or to evaluate what he sees and hears. He becomes almost an imbecile. Silent. Inarticulate. His belief becomes for him a perfect training ground for losing the forest from the trees, and an active process against cultivating the ability to think for oneself. He is the oddest of men. Steven’s Lord and Master—Darlington—is a World War I veteran and an honorable man. Darlington lives his life by old-school English notions of honor and fair play and, in his own kind of malaise-by-personal-credo, is slowly duped over the course of the 1920s and 1930s by hungry, aggressive Germans working to convince him their severe punishment following World War I had been too harsh, and entitled them to some special considerations in rebuilding their country. In their willful ignorance and bliss-by-personal-code-of-honor, Stevens and his butler make the perfect pair. What becomes important to the story is the fact that Darlington is slow-cooked into a fully finished Nazi Collaborator, believing all along he had merely been helping the German people get their economy back on its feet. At one point he dismisses two young, German-Jewish refugee women from his service at the request of his Nazi friends. He knew it was wrong and had a chance to stop the proceedings there but, like Stevens, he buried his hand in the sand and soldiered on. Stiff upper lip, and all that. Stevens never thought what he was helping along would lead to war or genocide, but it does. He and his family’s good, old names are disgraced, and both he and Steven’s had every opportunity to see it coming. But their personal oaths got in the way. “Tell me, Stevens, don’t you care at all?” Mr. Cardinal asks the Butler one night. Cardinal is an intelligent young man, a warm friend to Stevens, and happens to be Lord Darlington’s God Son, the child of a now-deceased Army veteran Darlington had served with during the Great War of fourteen-to-eighteen. “Good God, man, something very crucial is going on in this house. Aren’t you at all curious?” Cardinal asks the butler as he unsuccessfully tries to coax Stevens to set down his tray for a moment, and take a glass of bourbon with him. Cardinal is making a desperate attempt to explain the very decisive situation Stevens has been staring and listening to but somehow not seeing. Cardinal was a working newspaperman and columnist in the 1930s as his godfather Darlington sped toward the abyss. He had been to Germany and knew exactly what was happening under Hitler's regime. He sees the war coming and is horrified by Darlington’s role in aiding the Nazis. Cardinal cannot fathom how Stevens, an awfully intelligent man who has witnessed everything his employer has been doing, cannot see it too. Cardinal, being a patriotic Englishman, would serve his country’s military when World War II inevitably broke out and, as we find out later from an emotionally taciturn Stevens, was killed by the German army in Belgium. Does Stevens feel what should have been this deep personal bereavement? Cardinal was his friend, and a good lad grown into a sound young man. He did not deserve to die in that war. Maybe Stevens does feel it, but he is not capable of showing it, not like the rest of humanity would be. “You care about his lordship. You care deeply, you just told me that,” Cardinal implores Stevens. “If you care about his lordship, shouldn’t you be concerned? At least a little curious? The British Prime Minister and the German Ambassador are brought together by your employer for secret talks in the night, and you’re not even curious?” Stevens was not curious, at least not enough to betray his iron-clad credo for the life well lived. He is there to service his employer, not ask silly questions about war and death on an industrial scale. That was not his business. The book’s final blow hits home when Stevens reunites for a single afternoon with the former Miss Kenton, known now as Mrs. Benn for some twenty odd years. She had left Darlington Hall and married after exhausting herself pursuing an epically oblivious Stevens. Their interactions were often excruciatingly painful, with Miss Kenton exhausting herself in the effort to get Stevens to act like something beyond professional butlering and housekeeping existed in the world as the basis for a relationship. A secret robot programmed to butler may have shown more humanity, just to keep suspicion down, than Stevens seemed capable of. At one point, after Miss Kenton’s aunt had died, an aunt who had raised her up like a mother, Stevens consciously decides to offer her some emotional support. Miss Kenton, after all, had closed Steven’s father’s eyes after the man had died upstairs in Darlington Hall. Steven’s had not been able to go up to say farewell, you might have guessed, because the good lord was throwing a critically important gathering at the hall and Steven’s was in service. There is no time to say farewell to fathers under those circumstances. Miss Kenton had performed that deeply personal act of respect for the dead, and cried on his behalf. Stevens, for his part, never stopped working. Was Stevens repressing profound emotions, or did he not really feel anything at all? Miss Kenton believed he was shoving everything down. The reader goes without benefit. But in trying to show Miss Kenton he cared, Stevens actually ended up quibbling over small details he had noticed were being neglected by her housekeeping staff at Darlington, and criticizing her oversight. It was an epic, bewildering failure. Miss Kenton knew he had meant to console her, she could feel it, but even she was astonished at how completely he had destroyed his ability to interact like a normal human being. The exchange ended this way, according to Stevens, who never quite figured out what went wrong: “Miss Kenton looked away from me, and again an expression crossed her face as though she were trying to puzzle out something that had quite confused her. She did not look upset so much as very weary. Then she closed the sideboard, and said: ‘Please excuse me, Mr. Stevens,’ and left the room.” Their last meeting happened on a rainy day near the sea at Weymouth, where Stevens had gone to see if Mrs. Benn might return to Darlington Hall. In all her letters to him the most he had managed to extract was that perhaps she wanted to work together again—not that she loved him, or wanted to be near him as a human being, never that, which is what she had meant. Stevens was so repressed he made Miss Kenton feel odd about expressing her human feelings, too. During this last conversation Mrs. Benn admitted she had three times actually walked out on her husband—a boring but decent man who she had never really loved—while dreaming of a better life. “For instance, I got to thinking about a life I may have had with you, Mr. Stevens. And I suppose that’s when I would get angry over some trivial little thing and leave. But each time I do so, I realize before long—my rightful place is with my husband. After all, there’s no turning back the clock now. One can’t be forever dwelling on what might have been.” Stevens admits her bald-faced confession had momentarily struck him dumb. He sat for a few moments trying to take it all in. But in the end his credo, his training, the gray ashes that served for emotions, saved him. They always did. But for a passing moment he even admitted feeling something deeply. “As you might appreciate, their implications [her words] were such as to provoke a certain degree of sorrow within me. Indeed—why should I not admit it?—at that moment my heart was breaking.” Of course, instead of following up on that epiphany, the chance at real human companionship, he bid her a dignified farewell and put her on the bus home. He did it all like a gentleman, of course, oh it was most like a gentleman. Lord Darlington would have been proud. The book does in the end decide to haunt you with the strong possibility that a reckoning of some kind is coming to Stevens after all these years. He has let on over the course of the story that he might know more than he is willing to say about mistakes that were made at Darlington Hall. He had not been as blind as he had made out. “The fact is, of course, I gave my best to Lord Darlington. I gave him the very best I had to give, and now–well—I find I do not have a great deal more left to give.” While sitting on a bench in front of the sea with a total stranger who had also been a butler, though only a minor one, Stevens bursts into tears. It comes as a real shock, both because the conversation had been casual but more so because Stevens had never so much as smiled from a pure feeling, let alone wept. Stevens let it pour out: “Lord Darlington wasn’t a bad man at all. And at least he had the privilege of being able to say at the end of his life that he made his own mistakes. His lordship was a courageous man. He chose a certain path in life, it proved to be a misguided one, but there, he chose it, he can say that at least. As for myself, I cannot even claim that. You see, I trusted. I trusted in his lordship’s wisdom. All those years I served him, I trusted I was doing something worthwhile. I can’t even say I made my own mistakes. Really–one has to ask oneself—what dignity is there in that?” That is a fatalistic admission of almost-Greek dimensions. All his life he had cultivated “a dignity in keeping with his position,” only to find, in the end, he had had no real personal dignity at all. He had been a blind follower of someone else's life, and the man he'd picked to follow had been a well-intentioned fool who did real damage to people. The elegiac tone of the story, the end-of-something feeling, is deeply poignant. The era itself, the century for that matter, was one where faith in a certain decency, the belief in a semi-benevolent and even Divine concern for human affairs, was butchered for keeps. Many of the simple insights the book offers are valuable: in the prosaic way Nazi Germany was allowed to grow and come to fruition; how good men who did not think it through were exploited by bad men who did. The story of this butler, so odd and eccentric, so unexpectedly moving. What a strange idea Ishiguro had to write it at all. The book has that magical power of great literature that forces you to ask: Where did it come from? Why is it here? Why was it dreamed up at all? Well, why not read the book for yourself, maybe you will solve the mystery.

0 Comments

“You can take off your hats now gentlemen, and I think perhaps you’d better. This is not a legend, this is a reputation—and seen in perspective, it may well be one of the most secure reputations of our time.” —Stephen Vincent Benet at the death of F. Scott Fitzgerald in 1940 In Hollywood, that mostly mythical town where F. Scott Fitzgerald died aged 44, there is nothing of the man left to visit. The house where the heart attack took him in his reading chair on a lazy Sunday afternoon is just a house on a quiet, cedar shaded street south of Sunset Boulevard. There is no sense that the great writer set off there for the studios, or worked hard hours in the mornings on his last novel, which would have been great had he finished before his heart, which he claimed had dried up years earlier, finally killed him. In St. Paul, Minnesota, where he grew up, there is plenty left of him, and walking maps with routes have been printed up to guide you to the old haunts. If you get there, you should walk them. It is a fine, northern plains capital city anyway, and the old streets Fitzgerald wrote about sit high on the bluffs over the broad Mississippi River looking out. The train station is there, too, where I have departed and returned many times on James J. Hill’s Empire Builder route to Chicago. Once you are catching trains out of St. Paul headed east and back you are getting pretty close to Fitzgerald and can imagine just about everything you need to about America in those big booming years after World War I. You will have the time to do it on a slow train over the prairies, just like they’d had. Fitzgerald was born in a solid-looking brownstone with terraces of arches in old St. Paul, and 44 hustling years later he died in Hollywood, nearly forgotten and written off as a hopeless, cracked up drunk. All that came in the middle—the stuff of myth about a rise and fall and then a struggle to reclaim a place at the Big Parade—was the man’s life. Every year there is a little less of the haunted, diminishing trail of his well documented course over the earth, but the writing, at least, should last forever. Fitzgerald was an old school craftsman, the ones who wrote their first drafts in pencil, smearing their hands across the gray lead as they went. Those handwritten pages were then banged into typescripts, which had to be whittled down once more by the draftsman who knew there was a difference between what sounded good as a concept and what could actually be built and sold. Those pages, by now already layers of drafts, went to the printer to become galleys, which were re-scrutinized and chiseled at once more. Then they became proofs and were planed, sanded, and had the finishing work done right up until the books were set for publication. Even then, he knew he could have made it better. It was never as good as it could have been. Fitzgerald put everything he had into everything he wrote. Short stories pulled a precious bucketful from that well of experience and wisdom that filled only with time and could not, with a clear conscience, be faked. In his best years, he said he could get out eight or nine short stories before the well needed a new spring. Then, he set out with a divining rod and dug trenches until he struck home. In the end, he left 160 stories and four-and-a-half novels behind to prove he had worked. That is not something to turn your nose up at. And there is the challenge of writing to last—it is a game for the insatiable and brutal perfectionist. Fitzgerald’s work was so well built it has outlived the literary culture he wrote for. Those days are gone, kicked over like a dying campfire by indoors people who do not need an open flame, or even understand what it had meant to those who warmed themselves around its glow. Those who want to write to those standards now have to be even stronger than those very strong people who came before, because they will be the loneliest in the history of a lonely profession. The writing will never be as good as it was then; it can’t be. It is something like the old wooden shipbuilders who hammered together their vessels because that was the only way it was done. Now, the people who protected that ancient wisdom are dead and the new builders, through not much fault of their own, are making copies of copies without anyone with enough knowledge still around to say whether they have gotten it right. But Fitzgerald had those two things he needed to have to survive: courage and fortitude. Nothing more is needed to prove it than the whole wreck of his life after 1930, and his writing on in the face of his own living obscurity. His dreams turned out hollow and broke up. His wife Zelda broke down and went insane. With all that had come before still alive somewhere in her deteriorating mind, she wrote him from a sanitarium: “I love you anyway—even if there isn’t any me or any love or any life—I love you.” His daughter Scottie went to live with his agent and close friend, who respected Fitzgerald’s gift enough to take that burden, but it must have been a humiliation. Then, he cracked up himself and, in financial and emotional desperation, wrote about it for money. For that, he was ripped publicly by friends and was branded definitely washed up. It was a national story that the bright light had gotten prematurely dim. The collection of essays are some of his best and rawest work. He laid his soul bare and then took the group beating an act like that always inspires. Bankrupt, artistically and actually, he left for Hollywood believing he could make it work, found a beautiful woman there for animal companionship, and then struggled to turn out good scripts for the studios. But he wrote on—he wrote for its own sake because it always was his defense against the abyss. All this was bitter wisdom. Fitzgerald found out the price for losing your way once was years of toil to rediscover the path. That’s a lesson this generation knows as well as Fitzgerald did. But if you want endurance, picture the man Fitzgerald in Hollywood, across from Budd Schulberg at the Brown Derby talking brass tax on screenplays for movies! This was a hobbled Poseidon helping fishermen unload the day’s catch. What about all that lay behind him? The Roaring 20s, the Boom: New York, Paris, the Riviera, Rome, Africa. Big ships back and forth across the ocean with his famous wife and daughter; brasseries on the Left Bank and hotel bars in one of the world’s greatest towns with James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, Ernest Hemingway, Ford Madox Ford and Dos Pasos for company amongst a full-scale migration of touring Americans. The nights there, the unhealthy dissipation and the good, healthy work to save it, the novels, the acclaim, the huge fame, the photographs and newspapers following his life. The Old Greeks used to say something about never counting a man’s life happy until it was over. Sometimes the blows come early or late, but you know one thing for certain—they are coming. But through it all Fitzgerald stayed true, even if he could not always hew strictly to his principles. He wrote that the thing about life was not chasing pleasure, but satisfaction from doing one thing as well as you could, and making that burnt offering to the gods in exchange for immortality. The satisfaction was in the trying. Well, he did it, and the work will stand. Fitzgerald died—like Gatsby—still in the saddle, still dreaming the big dream. Hope was never lost. He was working on a book he believed would be one of his best. And it would have been—you can read what he had—it was good. The painful irony is that his heart failed him just when he had started to really grow up. Reality had horsewhipped the idealism he had thought he needed when his flesh wasn’t scarred over or tough enough to take the whipping. It had knocked him down for much of his 30s but he had roughed over and risen up from the ashes to try again. Like Gatsby, no amount of disillusionment could kill what he had believed was important in life—he saidnever lost sight of the Green Light. It is a literary footnote that the writer Nathanael West died in a car wreck the day after Fitzgerald. He had been on his way back to Los Angeles to offer the man farewell. In life, they had been friends. They two went off together then, wherever people go when they die, drinking a whisky and soda for its own sake and talking about how a writer could reach higher, run faster, jump further—until one fine day . . . . . The reason I created this blog was to weigh in every week on Ulysses while I read it. Provide real wisdom, some profound meditations on the meaning of it all. That hasn't gone to plan, but in my defense there's very little that's better for knocking down any feelings of pride in discipline you might have had than setting yourself a regular task that you have no experience with. I've never blogged before and never even really liked the idea of it—yet, here I am.

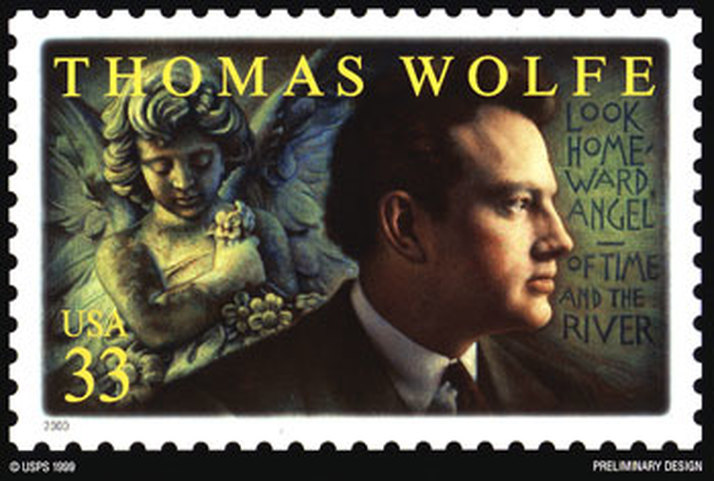

There will be more written on Ulysses than the original entry, let there be no doubt, but not tonight. Tonight I wanted a quick word on Thomas Wolfe, the original. The thyroid-giant who schooled at North Carolina-Chapel Hill and died at 39 having written 10-million words over four books while driving the greatest editor this country ever had into an early grave. It wasn't Wolfe's fault, really, but Maxwell Perkins of Charles Scribner's House spent too much time trying to talk sense into this garrulous behemoth. Wolfe wrote right out of the starting gate with the freedom of Steven King after fifteen best sellers. Words flowed like cheap wine and never stopped. Look Homeward Angel, his first novel, is physically an over-sized book and it goes 508 pages. He never wrote one shorter than that. Wolfe had some childish idea that he couldn't be edited, that he had too much to say and that only he knew how to say it. He fought for every word, which girded every paragraph that reinforced the very foundation of the novel. It all had to stay, man! I would call him the Lars von Trier of letters but Wolfe had real talent. Wolfe was like the Hell of a Wild Thoroughbred that every trainer bought at claiming price thinking he would be the one to break it and gather glory, but it never happened. That horse was wild. Then, like that, Wolfe was dead. No one reads his books anymore because they're too ponderous, but there is real profundity there if you care to look. Fittingly, Wolfe said the best things he ever said before his first book even fully begins. He turned over his cards early and, luckily for him, he was dealt the nuts Full House. Unluckily, he never learned to play that monster right. But enough about that. First, Wolfe explains fiction. In a title page section titled: "To the Reader" But we are the sum of all the moments of our lives - all that is ours is in them: we cannot escape or conceal it. If the writer has used the clay of life to make his book, he has only used what all men must, what none can keep from using. Fiction is not fact, but fiction is fact selected and understood, fiction is fact arranged and charged with purpose. Dr. Johnson remarked that a man would turn over half a library to make a single book: in the same way, a novelist may turn over half the people in a town to make a single figure in his novel. There you have it, Wolfe on the Art of Fiction. And it was true, he only wrote about people he knew and some of them didn't like it. But only those involved knew who they were in the books, Wolfe was good enough to change the names. And he wrote well, which must have been some consolation. Second, Wolfe writes a transcendent piece of verse on the page before the novel begins and gives out everything he brought to the world of books - which is the world itself preserved in its most permanent form. That is the best any new writer - a serious writer, that is - can do. He collects everything that came before him and finds something new to add to the old, old world. If he's good and maybe more, if he's lucky, he will stick around for quite a while. Wolfe was light on luck, in the end. But here it is: . . . . A stone, a leaf, an unfound door; of a stone, a leaf, a door. And of all the forgotten faces. Naked and alone we came into exile. In her dark womb we did not know our mother's face; from the prison of her flesh have we come into the unspeakable and incommunicable prison of this earth. Which of us has known his brother? Which of us has looked into his father's heart? Which of us has not remained forever prison-pent? Which of us is not forever a stranger and alone? O waste of loss, in the hot mazes, lost, among bright stars on this most weary unbright cinder, lost! Remembering speechlessly we seek the great forgotten language, the lost lane-end into heaven, a stone, a leaf, an unfound door. Where? When? O lost, and by the wind grieved, ghost, come back again. And can you beat that?  That's James Joyce—the cold Outfit killer in the eye patch—and his dame, Nora Barnacle. When you add in their all-encompassing outlaw ethos she could be gamely called his moll. That makes these two the Bonny and Clyde of the literary scene, which in normal times is the nerdy sanctuary of introverts who need real social anxiety allowances in order to function. Of course there are plenty of fine exceptions to that general rule, but stereotypes don't come from nothing. That picture is great for my purposes because I didn't want the first to be of James Joyce wearing coke-bottle glasses that presented him as a sort of confused, semi cross-eyed owl who'd had another mouse escape on him. There are plenty of those portraits; tend to turn people off. Joyce's eyes were awful and they got worse all his life. Had many eye surgeries in a losing effort to stay ahead of creeping blindness. Excessive reading in bad light wears down the eyes, but doctors now say the great writer likely had syphilis. The bad effects of that devilish "Cupid's disease" ruined more than one good man who enjoyed professional women in the days before penicillin was used to treat the infection. Ironically, Barnacle wasn't a big reader and intellectually she was not outfitted—nor was she interested in—appreciating her husband's books. He liked her because she was clever like a good, practical peasant woman, had guts or not enough brains to know what she was doing took guts, and was good in the sack. She had personality qualities that were his opposite, which attracted him. Also, she didn't mind, or managed to accept, Joyce's unusual mating proclivities and obsessions that he blamed the Jesuits for instilling through their very-Catholic denial of the wholesomeness of a man's built-in drive to hide the devil as often as the urge came. In the capacity of not understanding Joyce's books, Barnacle joined millions of others. Those who read Joyce with pleasure are maybe what Stendhal meant when he mentioned the happy few. This blog is getting off two weeks after the reading sessions began at Newberry Library, 60 West Walton Street, Chicago, The library itself is a place that raises you up by its personality. It's a grey granite, arched hulk set back from Washington Square Park on the Near North side. Last week I approached its eastern face through big, starry snowflakes falling over the spire of Harvest Cathedral with the library framed in city-winter light beyond it, which was a sight to remember. It's stately and pompous in a way that won't put off the common slob or the scholar. It's architectures is something Spanish or Romanesque—makes one look up and contemplate the meaning behind things. |

Mark SchipperAmerican writer. Archives

December 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed