Lane football field would be named for 1912 grad who was 1st Black QB, coach in NFL under alumni proposal

*This is the article as it appeared on the Chicago Sun-Times website*

Lane football field would be named for 1912 grad who was 1st Black QB, coach in NFL under alumni proposal Frederick Douglas

“Fritz” Pollard’s time to be recognized “is so long overdue,” said Lane Tech College Prep’s athletic director.

By Mark Schipper

By Mark Schipper

Frederick Douglas “Fritz” Pollard set the sod ablaze on gridirons across the United States in the first decades of the twentieth century, running as a sensational vanguard for Black American athletes at every trial.

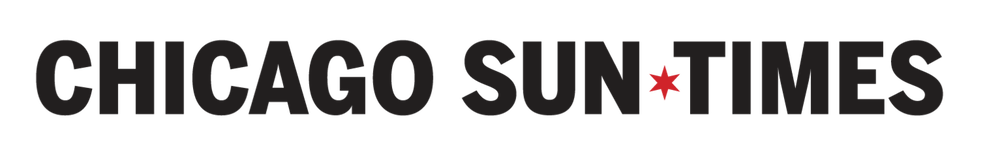

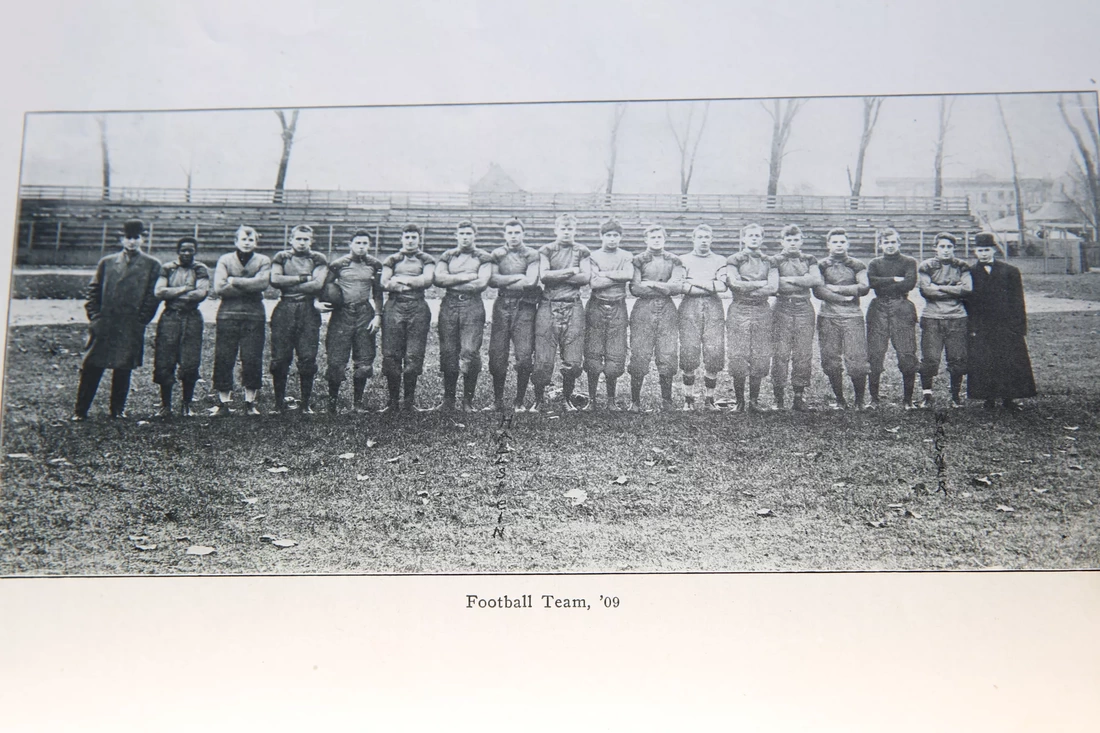

Pollard’s electrifying odyssey began at Lane Tech High School, where he was a three-sport phenom in the class of 1912, lettering and excelling over multiple varsity seasons in football, baseball and track.

He went on to star in college football and in the Rose Bowl and later played in the inaugural season of what became the National Football League. By the time his athletic journey ended, Pollard had carved his name in stone, as the first the first Black professional quarterback and the first Black professional head football coach. He was enshrined in both the college and professional halls of fame.

Now, a century after his exploits first drew national attention, the alumni association at Lane Tech wants to immortalize their historic letterman by renaming the school’s football field after Pollard.

‘Dream to name field after him’“It’s our dream to name the field after him — Fritz Pollard Field at Lane Stadium — and have a dedicated plaque right on Addison Street, so everybody going by could see it and ask questions about it and know about it,” said Michelle Weiner, a 1976 Lane Tech graduate and president of the alumni association.

Pollard’s electrifying odyssey began at Lane Tech High School, where he was a three-sport phenom in the class of 1912, lettering and excelling over multiple varsity seasons in football, baseball and track.

He went on to star in college football and in the Rose Bowl and later played in the inaugural season of what became the National Football League. By the time his athletic journey ended, Pollard had carved his name in stone, as the first the first Black professional quarterback and the first Black professional head football coach. He was enshrined in both the college and professional halls of fame.

Now, a century after his exploits first drew national attention, the alumni association at Lane Tech wants to immortalize their historic letterman by renaming the school’s football field after Pollard.

‘Dream to name field after him’“It’s our dream to name the field after him — Fritz Pollard Field at Lane Stadium — and have a dedicated plaque right on Addison Street, so everybody going by could see it and ask questions about it and know about it,” said Michelle Weiner, a 1976 Lane Tech graduate and president of the alumni association.

The school, which recently moved to retire its Indians moniker and mascot, is receptive to the idea.

“This is something so long overdue,” said Nick LoGalbo, a 2001 graduate of Lane Tech who is the current boys basketball coach and the school’s athletic director. “We have such a great athletic tradition, we’re 112 years old, and Fritz Pollard’s story is so important. It’s overdue but also very timely.”

The alumni association’s plan was presented Thursday night to the Lane Tech Local School Council, where it was received enthusiastically.

“We’re planning to present a resolution on Fritz Pollard and in support of this field proposal at our next board meeting,” said Benjamin Wong, a 1992 Lane Tech alumnus and member of the LSC.

The idea for dedicating the field to Pollard was sparked in March during a discussion on the alumni Facebook page.

“We posted some information on Fritz Pollard, and the alumni went crazy, the post caught fire,” Weiner said.

The alumni group will eventually present its formal plans to the sports administration team at Chicago Public Schools, the office responsible for running and maintaining facilities for the public school system.

Beyond renaming the field, ideas range from putting up a sign or plaque to erecting a statue of Pollard outside the stone stadium.

“If this all goes through like we’d like, I’d love to see the dedication happen with a big push from the athletic department and get our athletes engaged in understanding what type of celebration we’re having and how powerful it really is,” LaGalbo said.

Weiner agreed: “The opportunity to celebrate this amazing person, part of our family, is a chance to bring everyone together. We have five generations of living alumni, and most of them ... bleed the Myrtle and Gold. We have such a great heritage and so many great stories like this to tell, but Fritz Pollard was the first.”

“This is something so long overdue,” said Nick LoGalbo, a 2001 graduate of Lane Tech who is the current boys basketball coach and the school’s athletic director. “We have such a great athletic tradition, we’re 112 years old, and Fritz Pollard’s story is so important. It’s overdue but also very timely.”

The alumni association’s plan was presented Thursday night to the Lane Tech Local School Council, where it was received enthusiastically.

“We’re planning to present a resolution on Fritz Pollard and in support of this field proposal at our next board meeting,” said Benjamin Wong, a 1992 Lane Tech alumnus and member of the LSC.

The idea for dedicating the field to Pollard was sparked in March during a discussion on the alumni Facebook page.

“We posted some information on Fritz Pollard, and the alumni went crazy, the post caught fire,” Weiner said.

The alumni group will eventually present its formal plans to the sports administration team at Chicago Public Schools, the office responsible for running and maintaining facilities for the public school system.

Beyond renaming the field, ideas range from putting up a sign or plaque to erecting a statue of Pollard outside the stone stadium.

“If this all goes through like we’d like, I’d love to see the dedication happen with a big push from the athletic department and get our athletes engaged in understanding what type of celebration we’re having and how powerful it really is,” LaGalbo said.

Weiner agreed: “The opportunity to celebrate this amazing person, part of our family, is a chance to bring everyone together. We have five generations of living alumni, and most of them ... bleed the Myrtle and Gold. We have such a great heritage and so many great stories like this to tell, but Fritz Pollard was the first.”

Depicted as a Roman godIn team yearbook photos Pollard, the seventh of eight children who lived with his Native American mother and Black father in Rogers Park, is either the only Black face or one of two. His stature is remarkably small for a football player — listed between 5-feet-6 and 5-feet-9, depending on the program.

In one class yearbook cartoon, Pollard is depicted as the Roman god Mercury, the fleet messenger of the gods who wore the iconic winged sandals.

The metaphor worked well for Pollard, who would qualify in the low hurdles for the U.S. Olympic team in 1916 while running for Brown.

Pollard became a megawatt college football star after his teammates initially ostracized him both for being a freshman and Black, Pollard’s son has said in interviews. But once he had won them over, they went to great lengths to protect him from opposing fans and players, wearing baggy pants that matched Pollard’s look and even putting Black shoe polish on their faces, so it was not immediately apparent which player was Pollard.

In the 1916 season, the year after Pollard led the Bears to Pasadena and the Rose Bowl, the star halfback went berserk in games against Ivy League titans Harvard and Yale, gaining 292 yard and scoring three touchdowns, helping Brown to become the first team to knock off both schools in the same season.

Newspaper headlines across the East heralded Pollard as a star and the greatest show on turf. Legendary head coach and American football innovator Walter Camp named Pollard to his flagship all-American team, making him the first Black athlete to appear in the backfield.

Pollard was “one of the greatest runners these eyes have ever seen,” Camp proclaimed.

Following a brief period of uncertainty after college, where he had majored in chemistry and then trained to be a dentist, Pollard signed on with the Akron Pros of the brand new American Professional Football Association, soon to be renamed the N.F.L.

Along with the internationally famous Jim Thorpe — who twice addressed Pollard by a racial slur at their first meeting — Pollard was the league’s big draw, reportedly paid $1,500 a game in 1920 when the average yearly household income was $2,160.

In return for his fee, Pollard led the Pros to an 8-0-3 record, making the Akron squad the first undefeated professional football champion in league history in its very first season. Pollard was named a first-team all-pro halfback.

In one class yearbook cartoon, Pollard is depicted as the Roman god Mercury, the fleet messenger of the gods who wore the iconic winged sandals.

The metaphor worked well for Pollard, who would qualify in the low hurdles for the U.S. Olympic team in 1916 while running for Brown.

Pollard became a megawatt college football star after his teammates initially ostracized him both for being a freshman and Black, Pollard’s son has said in interviews. But once he had won them over, they went to great lengths to protect him from opposing fans and players, wearing baggy pants that matched Pollard’s look and even putting Black shoe polish on their faces, so it was not immediately apparent which player was Pollard.

In the 1916 season, the year after Pollard led the Bears to Pasadena and the Rose Bowl, the star halfback went berserk in games against Ivy League titans Harvard and Yale, gaining 292 yard and scoring three touchdowns, helping Brown to become the first team to knock off both schools in the same season.

Newspaper headlines across the East heralded Pollard as a star and the greatest show on turf. Legendary head coach and American football innovator Walter Camp named Pollard to his flagship all-American team, making him the first Black athlete to appear in the backfield.

Pollard was “one of the greatest runners these eyes have ever seen,” Camp proclaimed.

Following a brief period of uncertainty after college, where he had majored in chemistry and then trained to be a dentist, Pollard signed on with the Akron Pros of the brand new American Professional Football Association, soon to be renamed the N.F.L.

Along with the internationally famous Jim Thorpe — who twice addressed Pollard by a racial slur at their first meeting — Pollard was the league’s big draw, reportedly paid $1,500 a game in 1920 when the average yearly household income was $2,160.

In return for his fee, Pollard led the Pros to an 8-0-3 record, making the Akron squad the first undefeated professional football champion in league history in its very first season. Pollard was named a first-team all-pro halfback.

Pollard would become a player-coach in 1921, introducing to the professional game formations he had learned at Brown under Eddie N. Robinson. He was the first black professional coach in league history.

In 1923, he was named head coach of the Hammond (Ind.) Pros, another league first. During that 1923 season he also became the first black athlete to play quarterback in the N.F.L.

Despite being out of football since 1926, when the N.F.L. entered into its so-called “Gentlemen’s Agreement” era of 1934-1945 that essentially shut out Black players, Pollard created the Brown Bombers out of Harlem. They were a barnstorming all-black football team who played unofficial scrimmages against the top white teams of the day, always pressing for reintegration of professional football, where Pollard had excelled. The depression in 1938 ended the Brown Bombers era.

Following football, Pollard was a success in other fields. He opened what is said to be the first black investment firm — F.D. Pollard and Co. — in the United States. Later, he got into publishing, founding the N.Y. Independent News, a weekly tabloid for Black Americans.

He founded a coal distribution company in New York and, for a short time, managed a Harlem movie studio. He also managed on an individual basis some of the top black entertainers in the country, including Lena Horne and his former football teammate, Paul Robeson.

Pollard died in Silver Springs, Maryland, in 1986, at 92.

Mark Schipper is a Chicago-based freelance writer.

In 1923, he was named head coach of the Hammond (Ind.) Pros, another league first. During that 1923 season he also became the first black athlete to play quarterback in the N.F.L.

Despite being out of football since 1926, when the N.F.L. entered into its so-called “Gentlemen’s Agreement” era of 1934-1945 that essentially shut out Black players, Pollard created the Brown Bombers out of Harlem. They were a barnstorming all-black football team who played unofficial scrimmages against the top white teams of the day, always pressing for reintegration of professional football, where Pollard had excelled. The depression in 1938 ended the Brown Bombers era.

Following football, Pollard was a success in other fields. He opened what is said to be the first black investment firm — F.D. Pollard and Co. — in the United States. Later, he got into publishing, founding the N.Y. Independent News, a weekly tabloid for Black Americans.

He founded a coal distribution company in New York and, for a short time, managed a Harlem movie studio. He also managed on an individual basis some of the top black entertainers in the country, including Lena Horne and his former football teammate, Paul Robeson.

Pollard died in Silver Springs, Maryland, in 1986, at 92.

Mark Schipper is a Chicago-based freelance writer.