|

The reason I created this blog was to weigh in every week on Ulysses while I read it. Provide real wisdom, some profound meditations on the meaning of it all. That hasn't gone to plan, but in my defense there's very little that's better for knocking down any feelings of pride in discipline you might have had than setting yourself a regular task that you have no experience with. I've never blogged before and never even really liked the idea of it—yet, here I am.

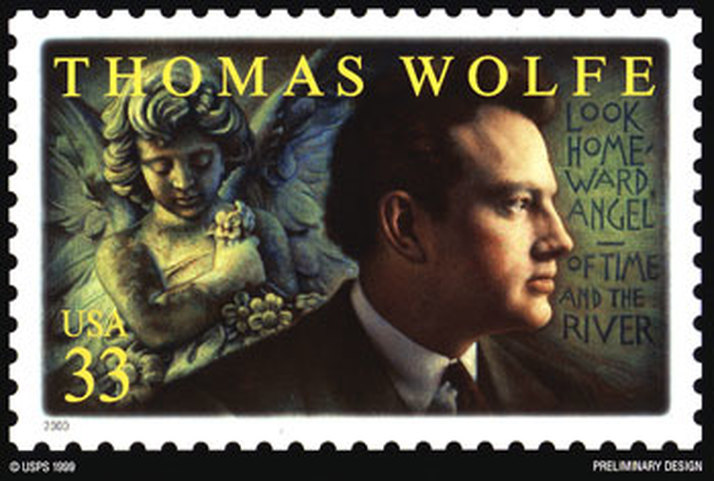

There will be more written on Ulysses than the original entry, let there be no doubt, but not tonight. Tonight I wanted a quick word on Thomas Wolfe, the original. The thyroid-giant who schooled at North Carolina-Chapel Hill and died at 39 having written 10-million words over four books while driving the greatest editor this country ever had into an early grave. It wasn't Wolfe's fault, really, but Maxwell Perkins of Charles Scribner's House spent too much time trying to talk sense into this garrulous behemoth. Wolfe wrote right out of the starting gate with the freedom of Steven King after fifteen best sellers. Words flowed like cheap wine and never stopped. Look Homeward Angel, his first novel, is physically an over-sized book and it goes 508 pages. He never wrote one shorter than that. Wolfe had some childish idea that he couldn't be edited, that he had too much to say and that only he knew how to say it. He fought for every word, which girded every paragraph that reinforced the very foundation of the novel. It all had to stay, man! I would call him the Lars von Trier of letters but Wolfe had real talent. Wolfe was like the Hell of a Wild Thoroughbred that every trainer bought at claiming price thinking he would be the one to break it and gather glory, but it never happened. That horse was wild. Then, like that, Wolfe was dead. No one reads his books anymore because they're too ponderous, but there is real profundity there if you care to look. Fittingly, Wolfe said the best things he ever said before his first book even fully begins. He turned over his cards early and, luckily for him, he was dealt the nuts Full House. Unluckily, he never learned to play that monster right. But enough about that. First, Wolfe explains fiction. In a title page section titled: "To the Reader" But we are the sum of all the moments of our lives - all that is ours is in them: we cannot escape or conceal it. If the writer has used the clay of life to make his book, he has only used what all men must, what none can keep from using. Fiction is not fact, but fiction is fact selected and understood, fiction is fact arranged and charged with purpose. Dr. Johnson remarked that a man would turn over half a library to make a single book: in the same way, a novelist may turn over half the people in a town to make a single figure in his novel. There you have it, Wolfe on the Art of Fiction. And it was true, he only wrote about people he knew and some of them didn't like it. But only those involved knew who they were in the books, Wolfe was good enough to change the names. And he wrote well, which must have been some consolation. Second, Wolfe writes a transcendent piece of verse on the page before the novel begins and gives out everything he brought to the world of books - which is the world itself preserved in its most permanent form. That is the best any new writer - a serious writer, that is - can do. He collects everything that came before him and finds something new to add to the old, old world. If he's good and maybe more, if he's lucky, he will stick around for quite a while. Wolfe was light on luck, in the end. But here it is: . . . . A stone, a leaf, an unfound door; of a stone, a leaf, a door. And of all the forgotten faces. Naked and alone we came into exile. In her dark womb we did not know our mother's face; from the prison of her flesh have we come into the unspeakable and incommunicable prison of this earth. Which of us has known his brother? Which of us has looked into his father's heart? Which of us has not remained forever prison-pent? Which of us is not forever a stranger and alone? O waste of loss, in the hot mazes, lost, among bright stars on this most weary unbright cinder, lost! Remembering speechlessly we seek the great forgotten language, the lost lane-end into heaven, a stone, a leaf, an unfound door. Where? When? O lost, and by the wind grieved, ghost, come back again. And can you beat that?

0 Comments

|

Mark SchipperAmerican writer. Archives

December 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed