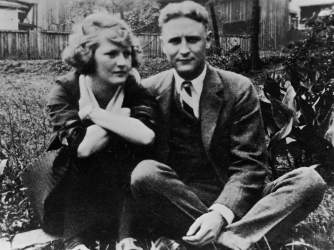

“You can take off your hats now gentlemen, and I think perhaps you’d better. This is not a legend, this is a reputation—and seen in perspective, it may well be one of the most secure reputations of our time.” —Stephen Vincent Benet at the death of F. Scott Fitzgerald in 1940 In Hollywood, that mostly mythical town where F. Scott Fitzgerald died aged 44, there is nothing of the man left to visit. The house where the heart attack took him in his reading chair on a lazy Sunday afternoon is just a house on a quiet, cedar shaded street south of Sunset Boulevard. There is no sense that the great writer set off there for the studios, or worked hard hours in the mornings on his last novel, which would have been great had he finished before his heart, which he claimed had dried up years earlier, finally killed him. In St. Paul, Minnesota, where he grew up, there is plenty left of him, and walking maps with routes have been printed up to guide you to the old haunts. If you get there, you should walk them. It is a fine, northern plains capital city anyway, and the old streets Fitzgerald wrote about sit high on the bluffs over the broad Mississippi River looking out. The train station is there, too, where I have departed and returned many times on James J. Hill’s Empire Builder route to Chicago. Once you are catching trains out of St. Paul headed east and back you are getting pretty close to Fitzgerald and can imagine just about everything you need to about America in those big booming years after World War I. You will have the time to do it on a slow train over the prairies, just like they’d had. Fitzgerald was born in a solid-looking brownstone with terraces of arches in old St. Paul, and 44 hustling years later he died in Hollywood, nearly forgotten and written off as a hopeless, cracked up drunk. All that came in the middle—the stuff of myth about a rise and fall and then a struggle to reclaim a place at the Big Parade—was the man’s life. Every year there is a little less of the haunted, diminishing trail of his well documented course over the earth, but the writing, at least, should last forever. Fitzgerald was an old school craftsman, the ones who wrote their first drafts in pencil, smearing their hands across the gray lead as they went. Those handwritten pages were then banged into typescripts, which had to be whittled down once more by the draftsman who knew there was a difference between what sounded good as a concept and what could actually be built and sold. Those pages, by now already layers of drafts, went to the printer to become galleys, which were re-scrutinized and chiseled at once more. Then they became proofs and were planed, sanded, and had the finishing work done right up until the books were set for publication. Even then, he knew he could have made it better. It was never as good as it could have been. Fitzgerald put everything he had into everything he wrote. Short stories pulled a precious bucketful from that well of experience and wisdom that filled only with time and could not, with a clear conscience, be faked. In his best years, he said he could get out eight or nine short stories before the well needed a new spring. Then, he set out with a divining rod and dug trenches until he struck home. In the end, he left 160 stories and four-and-a-half novels behind to prove he had worked. That is not something to turn your nose up at. And there is the challenge of writing to last—it is a game for the insatiable and brutal perfectionist. Fitzgerald’s work was so well built it has outlived the literary culture he wrote for. Those days are gone, kicked over like a dying campfire by indoors people who do not need an open flame, or even understand what it had meant to those who warmed themselves around its glow. Those who want to write to those standards now have to be even stronger than those very strong people who came before, because they will be the loneliest in the history of a lonely profession. The writing will never be as good as it was then; it can’t be. It is something like the old wooden shipbuilders who hammered together their vessels because that was the only way it was done. Now, the people who protected that ancient wisdom are dead and the new builders, through not much fault of their own, are making copies of copies without anyone with enough knowledge still around to say whether they have gotten it right. But Fitzgerald had those two things he needed to have to survive: courage and fortitude. Nothing more is needed to prove it than the whole wreck of his life after 1930, and his writing on in the face of his own living obscurity. His dreams turned out hollow and broke up. His wife Zelda broke down and went insane. With all that had come before still alive somewhere in her deteriorating mind, she wrote him from a sanitarium: “I love you anyway—even if there isn’t any me or any love or any life—I love you.” His daughter Scottie went to live with his agent and close friend, who respected Fitzgerald’s gift enough to take that burden, but it must have been a humiliation. Then, he cracked up himself and, in financial and emotional desperation, wrote about it for money. For that, he was ripped publicly by friends and was branded definitely washed up. It was a national story that the bright light had gotten prematurely dim. The collection of essays are some of his best and rawest work. He laid his soul bare and then took the group beating an act like that always inspires. Bankrupt, artistically and actually, he left for Hollywood believing he could make it work, found a beautiful woman there for animal companionship, and then struggled to turn out good scripts for the studios. But he wrote on—he wrote for its own sake because it always was his defense against the abyss. All this was bitter wisdom. Fitzgerald found out the price for losing your way once was years of toil to rediscover the path. That’s a lesson this generation knows as well as Fitzgerald did. But if you want endurance, picture the man Fitzgerald in Hollywood, across from Budd Schulberg at the Brown Derby talking brass tax on screenplays for movies! This was a hobbled Poseidon helping fishermen unload the day’s catch. What about all that lay behind him? The Roaring 20s, the Boom: New York, Paris, the Riviera, Rome, Africa. Big ships back and forth across the ocean with his famous wife and daughter; brasseries on the Left Bank and hotel bars in one of the world’s greatest towns with James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, Ernest Hemingway, Ford Madox Ford and Dos Pasos for company amongst a full-scale migration of touring Americans. The nights there, the unhealthy dissipation and the good, healthy work to save it, the novels, the acclaim, the huge fame, the photographs and newspapers following his life. The Old Greeks used to say something about never counting a man’s life happy until it was over. Sometimes the blows come early or late, but you know one thing for certain—they are coming. But through it all Fitzgerald stayed true, even if he could not always hew strictly to his principles. He wrote that the thing about life was not chasing pleasure, but satisfaction from doing one thing as well as you could, and making that burnt offering to the gods in exchange for immortality. The satisfaction was in the trying. Well, he did it, and the work will stand. Fitzgerald died—like Gatsby—still in the saddle, still dreaming the big dream. Hope was never lost. He was working on a book he believed would be one of his best. And it would have been—you can read what he had—it was good. The painful irony is that his heart failed him just when he had started to really grow up. Reality had horsewhipped the idealism he had thought he needed when his flesh wasn’t scarred over or tough enough to take the whipping. It had knocked him down for much of his 30s but he had roughed over and risen up from the ashes to try again. Like Gatsby, no amount of disillusionment could kill what he had believed was important in life—he saidnever lost sight of the Green Light. It is a literary footnote that the writer Nathanael West died in a car wreck the day after Fitzgerald. He had been on his way back to Los Angeles to offer the man farewell. In life, they had been friends. They two went off together then, wherever people go when they die, drinking a whisky and soda for its own sake and talking about how a writer could reach higher, run faster, jump further—until one fine day . . . . .

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Mark SchipperAmerican writer. Archives

December 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed